Outcomes are random…embrace it!

This post illustrates how outcomes are caused by both decisions, which set the probability of each outcome, and exceptional (or unexceptional) performance within that probability distribution. The main points are:

- Outcomes are, on aggregate, a random event

- Outcomes are the result of exceptionalism within a probability distribution

- Relying on good probability distributions leads to sustainable good outcomes

Outcomes are, on aggregate, a random event

You may have heard of randomness before in terms of rolling dice or flipping coins. You may even have heard of terms like the law of large numbers or the gambler’s fallacy. If not, no problem because the concept of randomness can be summarized by two important concepts:

- Every situation has a set of potential outcomes

- Every potential outcome has some probability of occurring

Take flipping a coin: the potential outcomes are heads or tails, each with a 50% chance of occurring. Or rolling dice: every number 1-6 has 16.66% likelihood of occurring.

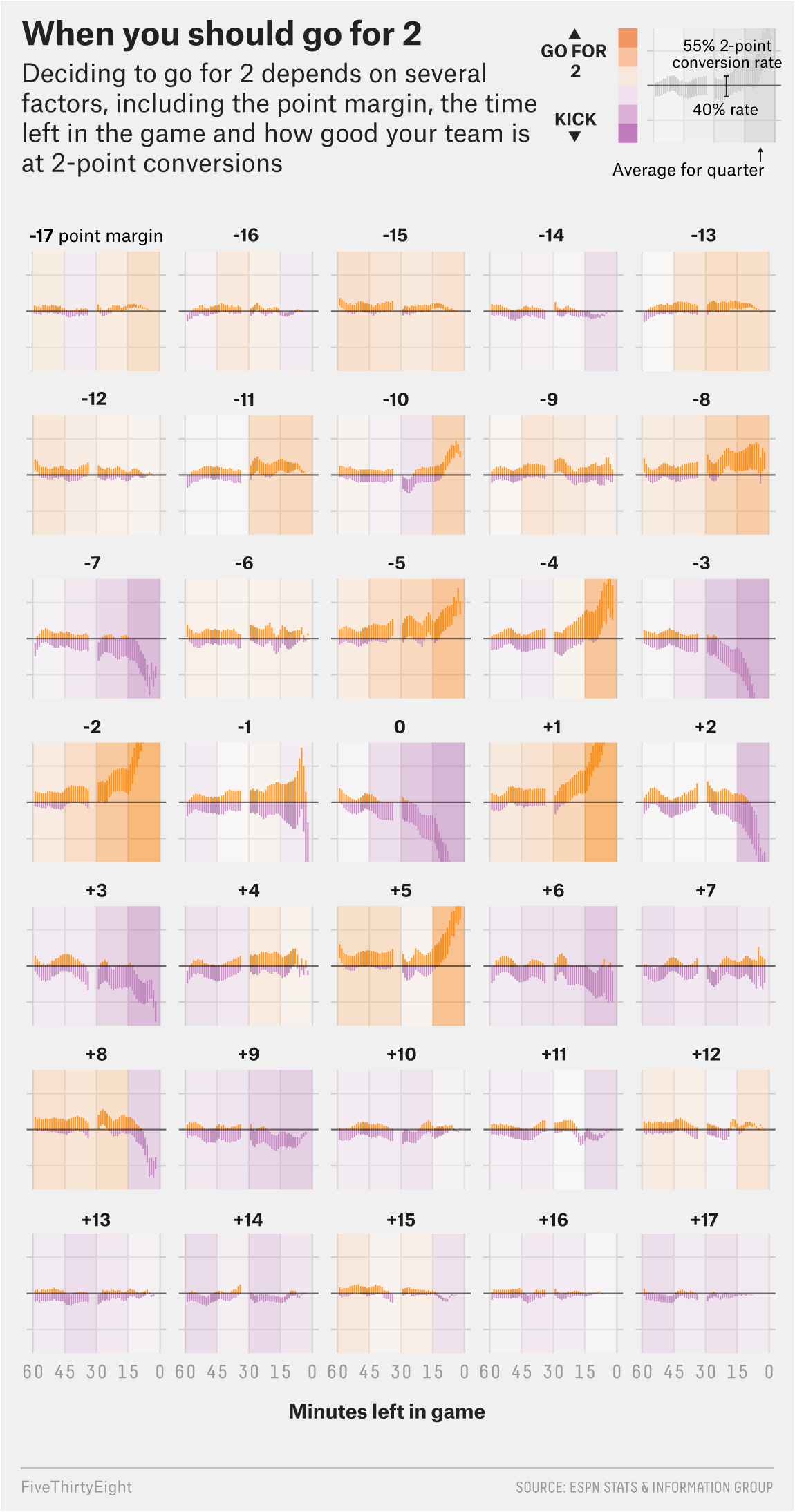

You can imagine that probabilities get much more complex than flipping coins, but at their base level every probability model is concerned with a situation’s potential outcomes and each outcome’s probability of occurring. The NFL provides a tangible example, where many teams use probabilities to decide if, after a touchdown, the team should kick an extra point of go for a two point conversion.

Some scenarios come close to purely random; over a large sample size no one can flip a coin much different than 50-50. But pure randomness cannot explain consistently exceptional results: how some companies are consistently better than others, how some teams win the big games, how some celebrities make more money. In reality, randomness is the context in which humans perform in, and human performance sometimes is exceptional.

Outcomes are the result of exceptionalism within a probability distribution

The concept that ‘all outcomes are random’ only goes so far, since we know that some people have consistently better financial, social, romantic, popularity outcomes than others. This phenomenon can be explained by exceptionalism – where people or teams excel within certain probability distributions.

The first key point to understand is the distinction between situations (aka probability distributions) and execution (aka exceptionalism). Situations are created by decisions, strategy, foresight; execution is the operation, day-to-day tactical performance. Another way to think about the distinction is that a situation is what we decided to do and execution is how well we are executing, given our prior decisions.

Let’s look at the relationship between decisions and exceptionalism in the context of two managerial decisions in a company:

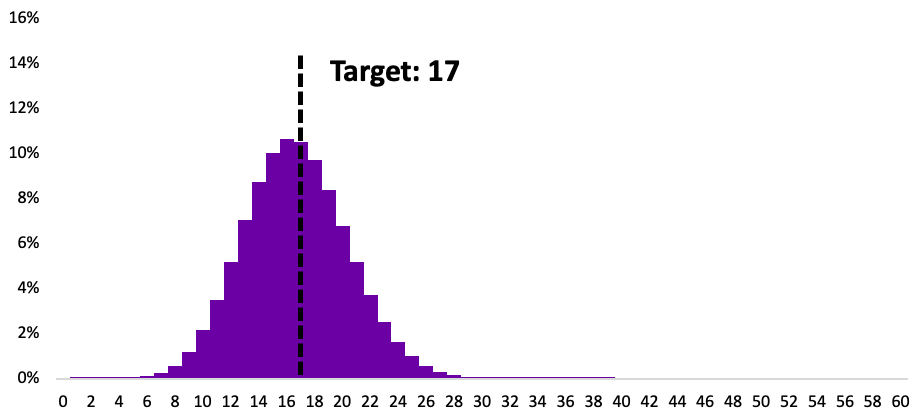

Let’s say you work for Dice Rolling Inc in the aptly-named Roll a Six department. Your department’s annual goals this year are considered tough-but-fair: the department is expected to roll a six at least 17 times in 100 tries.

Being an analytical person, you can quickly draw up the probability distribution of rolling a six the specified number of times in 100 tries, and determine your probability of hitting your goal (rolling a 6 at least 17 times) is 50.6%. In other words, you must perform in the 49th percentile to achieve your goal.

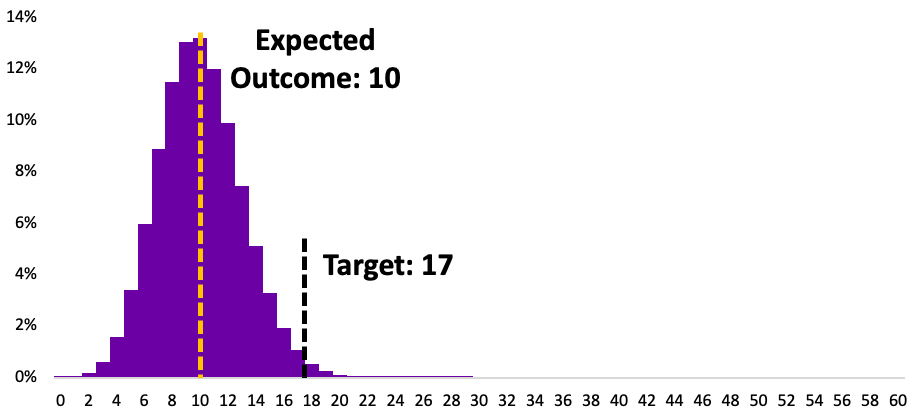

In a spurt of misguided thoughtfulness, your manager requires you to use 10-sided dice, citing the logic, “with more sides you have more opportunities!” Unbeknownst to said manager, his poor decision decreased your likelihood of rolling 17 sixes to 2.1%, and now you must perform in the 98th percentile to achieve your goal!

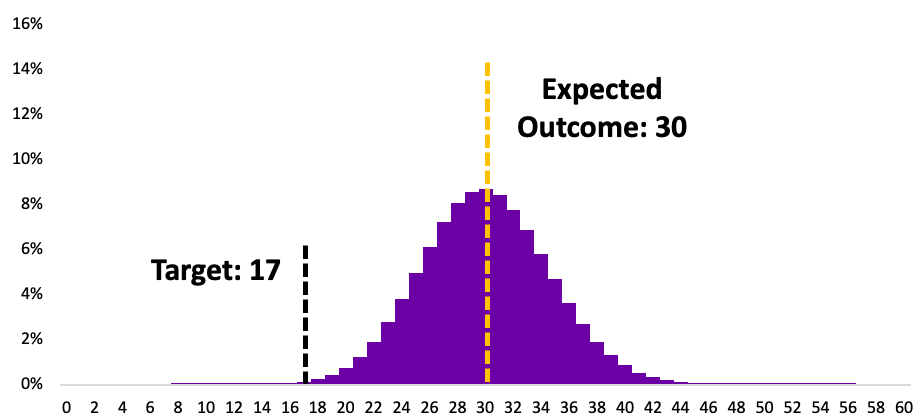

Your coworker’s manager took a different approach, reaching out to an old friend who procured some 10-sided dice that have sixes on three sides! Her great decision means that your coworker only needs to be 0.1% exceptional to meet the goal!

Undeterred by to poor odds, you spend hours analyzing the 10-sided dice and miraculously discover a secret rolling method (between the legs on a 12.2 degree incline) that allows you to roll exactly 17 sixes! Your coworker turns out to be phenomenally incompetent, and they also roll exactly 17 sixes. In this example both teams got the same results in different ways, when considering their decisions and exceptionalism.

| Manager | Decision | Required Exceptionalism |

|---|---|---|

| #1 | 10-sided dice | 97.9% |

| #2 | 30% dice | 0.1% |

One team’s results were driven by poor situations and exceptional performance, and the other team’s results were caused by great situations and poor performance. But which of these methods of producing outcomes is better?

Relying on good probability distributions leads to sustainable good outcomes

There are times when exceptional performances are required to get the outcome you want. An unorganized team may need to pull an all-nighter before a big sales pitch to land the deal; a poor-attendance student may need to cram all week to get a good grade; an undisciplined team may still produce great results on the field thanks to some big plays.

The reality is that results produced by exceptional performance will likely not last. Over a large sample, these results usually return back to the average of the probability distribution; think of a batter coming off of a hot streak, or one-hit-wonder musicians. Even if good outcomes can be sustained by exceptional performance, such consistent perfection takes an immense toll on people. In the dice example the team with the bad manager must consistently perform in the 98th percentile – who can do that in the long run?

Instead of relying on exceptionalism, individuals and teams should take the following steps:

- Identify where exceptionalism is required to get the outcomes they want

- Make decisions that improve those probability distributions before entering the executing phase

The unorganized sales team should focus on a standardized timelines and better communication so the deck is ready well in advance. The truant student should focus on improving attendance so they don’t have to cram. The team needs to get better at discipline or it will catch up with them. This principle is all about being intentional about the situations you end up in so you are not reliant on heroic performances for the results you want.

There is a scene in the TV show “The Wire” where the drug kingpin Avon is talking to his nephew about staying on top of his game and says:

See, the thing is, you only got to f**k up once. Be a little slow, be a little late, just once. And how you ain’t gonna never be slow? Never be late?

- Avon Barksdale

Avon needed to always be on, always alert, always one step ahead of the cops; he had to always be exceptional, and knew that it was impossible in the long run. When you rely on probability distributions, you are using math to your advantage, and good outcomes will come more naturally since they will be driven by your context, decisions, and surroundings rather than heroic individual effort.

Sustainable success comes from improving your probability distributions rather than relying on exceptionalism.